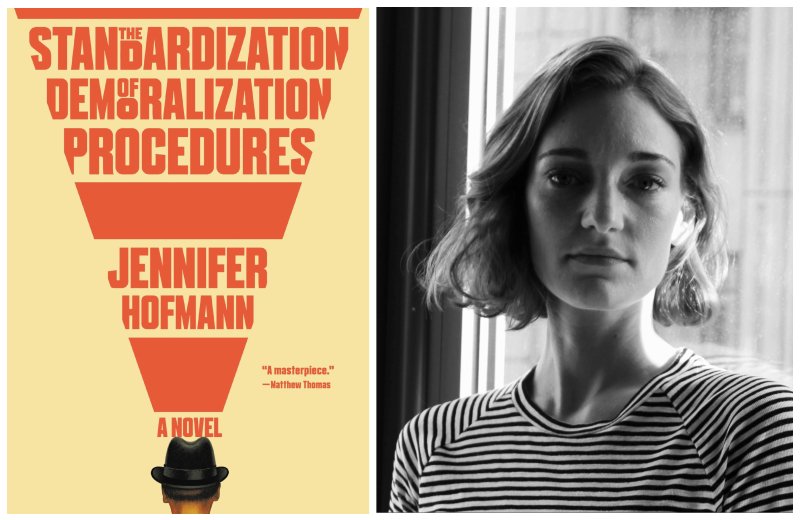

Interview with Jennifer Hofmann

“Be mindful of who and what you read, stop looking at what everyone else is doing, write as if you’ll never get published, and don’t ever take it too seriously. ”

Jennifer Hofmann is the author of acclaimed novel, The Standardization of Demoralization Procedures. The novel was reviewed by The New York Times as a “gripping debut”; The Washington Post calls it “a rare novel that encourages you to read as though your sanity depends on it.”

I read early chapters of The Standardization of Demoralization Procedures in draft form and its ending took me by surprise. How did you plan out your novel?

I had all major plot points mapped out from the beginning, including the ending. There were a few attempts at visualizing the storyline and characters on paper—sticky notes, diagrams—but I didn’t find that very helpful. In the end I held the entire thing in my head, dangling my way from point A to point B. I made life hard for myself, but it’s the only way I could strike a balance between following a rigid plotline and allowing for things to develop sideways.

Did any of your characters take a different turn to one you were expecting?

Yes and no. I chose these characters for their inherent contradictions. But the deeper I got into them the more they developed from schematic, cartoon-like people to three-dimensional beings. It’s all a bit like falling in love: letting initial superficial projections give way to reality. All of these characters turned from prop to person, which of course influenced their trajectory.

In his review in The Washington Post, Ron Charles wrote that the story of the novel “feels like descending stairs in an Escher drawing”; did you have any specific hopes for how the reader would feel reading the novel?

I think I’d have to differentiate between my hopes and what the story required in the end. My aim definitely wasn’t to build a disorienting narrative in which the reader couldn’t tell which way was up. But that’s ultimately what writing about this aspect of the GDR required, and what I ultimately believed the reader should carry with them throughout the experience. In other words, I found there was no way to write about the bureaucratic monstrosity that was the GDR government and all its tentacles without creating a sense of ominous unease and disorientation in the language and storyline. So rather than setting out to create confusion, I let the subject matter do what it would. I actually tried to bring sense into senselessness, if you can believe it.

How long did it take you to write the novel?

Depends on when you start counting. Attempts, first drafts, initial sparks of the story, about 10 years ago. The story as it stands here, start to finish, about 3 years.

What is your writing regime?

I’m a bit of a neurotic when it comes to writing: I get up early, get out of the house, and go read somewhere. When I get back, I immediately sit down and work. I treat returning home like going to the office. I’ve always worked from home, so there’s always been some self-trickery going on to stay disciplined.

Maya Angelou was reputed to write lying on a made-up bed with a bottle of sherry, a dictionary, Roget’s Thesaurus, yellow notepads, an ashtray and a Bible. I imagine that you have a similar set up when you write…What specific things do you like to have around you?

I wish it was sherry. I used to need cigarettes, which I’d also neurotically tied to writing, but I gave that up. Now I just need a clean desk and solitude, which sounds terribly boring.

How do you feel when you’re writing?

A bit ridiculous.

What is your procrastination activity of choice?

I have a list of things I’m allowed to procrastinate with. All of the items on that list are things I wholeheartedly do not want to do: taxes, bills, cleaning, answering emails. When I can’t help but procrastinate, I know I can only pick from that list, so I usually end up writing to avoid doing those things. That way I use writing to procrastinate from the things I’m allowed to procrastinate with. Sometimes I procrastinate inadvertently by getting into absurdly detailed, obscure research binges. It takes a while until I admit to myself that I’m not actually working, but self-indulging.

It strikes me that there may be some similarities between being a spy and being a writer. Would you agree, and if so, in what regard?

That’s a terribly good question. It depends on what kind of spy you’re talking about. If you’re the kind of operative ordered to observe and analyze a subject’s character and objectives, then you’re spot on. Spying—in that sense—and writing both require you to think two, three steps ahead in terms of people’s motives, as well as larger, less tangible interconnections. The objectives are quite different, of course, and as a writer you’re ideally not following orders as a tiny cogwheel in a giant, faceless apparatus fueled by questionable motives.

Like Zeiger, are you an eavesdropper?

Aren’t we all? I’m not hiding behind bushes, eavesdropping, of course. But if I stumble into something, of course I’ll stop and listen.

The Standardization of Demoralisation Procedures is remarkable in its historical research; how did living in Berlin influence your writing?

Without living in Berlin I would have never had access to the many personal stories people have shared with me along the way. There’s just no way you can find these anecdotes in books. In terms of true influence on the writing, speaking German—my mother tongue, if you will—day in and day out, influenced the novel’s voice. You can’t write a novel about a very German man, set in a very German city without letting the language infuse the book.

What can a teacher give a writer in a creative writing class?

I’m not sure if a teacher can teach someone how to write, but maybe they can teach them a bit about how to think.

What would you say are the most important qualities of an editor?

Objectivity, empathy, endurance, and genuine passion for the work.

Do you feel part of a literary community?

I have a lot of writer friends, but I don’t consider myself part of any literary community. I don’t particularly enjoy speaking about writing all that much, so I don’t consciously seek out the company of a community.

Who are the writers that you admire, and why?

Off the top of my head: Joseph Heller, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Thomas Mann, Graham Greene, Mikhail Bulgakov, Vladimir Nabokov, Herta Müller, Malcolm Lowry, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Don DeLillo, Laszlo Kraszhnahorkai, …

If I got into why I admire them, I think we’d end up with a PhD thesis.

Which books did you enjoy most over the last year?

John Updike’s THE COUP. It’s a short novel set in the 60s in a fictional African country, written through the eyes of the nation’s self-conscious dictator. There is Soviet intervention, American meddling, rampant corruption, sexism, you name it. The novel would most likely never be published today—too nuanced in its politics, too ambiguous in its moral judgements—but it was a national bestseller when it came out in 1978. Remarkable how industry tastes have changed.

Which book should I run out and buy right now?

Maybe John Updike’s THE COUP? Ha!

What was the thing that most surprised you about the publishing process?

The care and passion with which my wonderful editor, Ben George at Little, Brown, approached the novel. Also, I was published during COVID and a burgeoning social justice movement, so everything about the process ended up being a surprise.

What is the most useful piece of advice, as a writer, that you have ever received?

Forget everything you’ve learned about writing.

What advice would you give to writers who are early in their career?

Be mindful of who and what you read, stop looking at what everyone else is doing, write as if you’ll never get published, and don’t ever take it too seriously.

What are you working on now?

A new novel, set in 1950s Bogotá.